Posted by Virus Bulletin on Aug 6, 2013

DNS caching causes attack to have a long tail.

Yesterday, visitors to thousands of Dutch websites were served an 'under construction' page that, through a hidden iframe, was serving the Blackhole exploit kit.

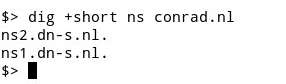

The sites were hosted by three hosting companies that share both a parent company and, more importantly in this case, nameservers for their clients' DNS records.

DNS, which translates domain names into IP addresses, is often described a 'the phonebook of the Internet'. But rather than one big phonebook, DNS actually uses many different phonebooks, or nameservers. For each domain, two or more nameservers are marked as 'authorative' - a nameserver that doesn't know a particular DNS record for a certain domain makes a request to one of its authoritive nameservers, the response to which is then forwarded to the client that made the original request.

In this particular case, hackers had managed to modify the DNS records for the authorative nameservers used by the hosting companies' clients. As a result, when a user visited one of thousands of websites, their browser would request the IP address for the domain to the ISP's DNS server. This would then forward the request not to the real authorative nameserver, but to a server hosted in France that was controlled by the hackers.

As is typical for these kinds of breaches, the attack took place in the middle of the night, at around 3:30am local time. It was discovered and subsequently rectified by the companies at around 6am and then picked up by SIDN, the .nl registry, at 8am.

However, the attackers rather cunningly set the TTL (time to live) for the requests at 24 hours. TTL allows nameservers to store responses in their own cache, rather than forward each request to the authorative servers. A TTL of 24 hours means that requests are stored in the cache for up to 24 hours - thus users could have been redirected to the malicious server until the early hours of Tuesday.

It is unclear where the root of the breach lies, though the providers have pointed their fingers at SIDN. More worryingly, the companies' status updates focus on the fact that their clients' websites were unreachable, rather than on the fact that many visitors who used unpatched software would have been infected with malware.

Of course, whatever hole was used to make the DNS changes should be closed. But the providers may also want to look into DNSSEC which cryptographically signs DNS responses. While attacks are possible where DNSSEC's private keys are stolen, in this case it would have prevented users from being sent to the malware-hosting website.

A more detailed write-up on the case (including details on the malware served) by Fox-IT's Yonathan Klijnsma can be found here.

Posted on 6 August 2013 by Martijn Grooten